Editor’s note: This is one of a series of articles that will run until Labor Day in advance of the Shelby County Historical Society’s Week of Valor, including the return to Sidney of the Vietnam Memorial replica wall and a Field of Valor featuring American flags in Custenborder Park. Flags for the Field of Valor can be purchased by calling 498-1653. The project commemorates 2015 as the anniversary of the beginning or end of several U.S. armed conflicts. This series will include stories about most of America’s wars. Today, a Sidney resident talks about his grandfather, who fought in World War I.

SIDNEY — Jim Hall, of Sidney, grew up living next door to his grandfather, Merton E. Hall, in rural Shelby County.

Merton taught Jim how to fish and how to hunt. He taught him how to work on cars. He helped Jim earn his Boy Scout merit badges.

One thing Merton didn’t do was talk about his experiences in World War I. That didn’t happen until well after Jim had served in the Vietnam War. Merton opened up about three months before he died in 1983.

World War I, the Great War, the War to End All Wars, began in 1914 when a Yugoslavian assassinated the archduke of Austria.

Austria declared war on Serbia. Germany, an ally of Austria, invaded Belgium and Luxembourg. England and France, allies of Belgium, were drawn into the conflict. By 1917, when troops from the U.S. began to participate following a German U-boat’s sinking of the luxury liner, Lusitania, Russia, Bulgaria and Romania were all at war, too.

Merton was drafted into the Army and served in Europe for 11 months from 1917 into 1918. His brother, Carlton, also served during the war. They had come from a family of military servicemen. Merton’s grandfather and uncle both fought in the Civil War, marched with Sherman through Georgia to the sea, were captured and survived the Andersonville Prison to return home from the war.

And the family’s service didn’t stop with Merton. His son, Gilbert, Jim’s father, fought in World War II before Jim saw service in Vietnam.

Merton had grown up as a neighbor to Ben LeFevre, a politician and counsel to Germany.

“He used to play at Gen. LeFevre’s house,” Jim said. As an adult, Merton worked as a letter carrier, which was the job he held when he entered the service. And he had been dating the woman who was to become his wife, Mabel.

His basic training took place at Camp Sherman near Chillicothe. While he was there, the camp suffered from a major Spanish influenza outbreak. Some 1,200 soldiers died of the disease and thousands more contracted it, but Merton escaped being ill.

He did not, however, escape sea sickness.

“On the ship over (to Europe), he spent most of his time with his head over the rail,” Jim said. In France, Pvt. Hall served in the Rainbow Division in the Meuse-Argonne offensive, which, according to Jim, was the longest line of defense on the Western Front.

It was trench warfare. Merton told Jim what it felt like to be confined to a trench.

“You couldn’t stick your head up or anything up for fear the Germans could see you,” Jim said. “He spent better than eight months in that trench. He wrote a letter to my grandmother every day. Can you imagine in that dirty trench finding a dark corner to write a letter?”

The offensive was the last assault on what was known as the Hindenburg Line, a German defense that stretched for several miles.

“Built in late 1916, the Hindenburg Line — named by the British for the German commander in chief, Paul von Hindenburg; it was known to the Germans as the Siegfried Line — was a heavily fortified zone running several miles behind the active front between the north coast of France and Verdun, near the border of France and Belgium,” according to History.com. “By September 1918, the formidable system consisted of six defensive lines, forming a zone some 6,000 yards deep, ribbed with lengths of barbed wire and dotted with concrete emplacements, or firing positions. Though the entire line was heavily fortified, its southern part was most vulnerable to attack, as it included the St. Quentin Canal and was not out of sight from artillery observation by the enemy. Also, the whole system was laid out linearly, as opposed to newer constructions that had adapted to more recent developments in firepower and were built with scattered ‘strong points’ laid out like a checkerboard to enhance the intensity of artillery fire.

“The Allies would use these vulnerabilities to their advantage, concentrating all the force built up during their so-called ‘Hundred Days Offensive’ — kicked off on Aug. 8, 1918, with a decisive victory at Amiens, France — against the Hindenburg Line in late September. Australian, British, French and American forces participated in the attack on the line, which began with the marathon bombardment, using 1,637 guns along a 10,000-yard-long front. In the last 24 hours, the British artillery fired a record 945,052 shells.”

At one point, Merton was slightly wounded by a piece of shrapnel. And he was fighting not far from where Sgt. Alvin York’s exploits were earning the latter the Medal of Honor. York was later considered the greatest American hero of World War I.

“He knew of Alvin York,” Jim said. But what Merton talked about was the guilt he, himself, felt for having killed someone.

“That really haunted him his whole life,” Jim said. “He had great pride in his country and was honored to have served his country.”

Just after the armistice was signed, Merton got to see Gen. “Black Jack” Pershing, the commander of the American forces in Europe.

When Merton returned to Sidney after the war, he married Mabel. They had two children, Gilbert and Irene, and he resumed his career as a letter carrier. He covered rural route No. 6 in a Model T and a horse-drawn buggy.

“He’d park the car and use the horse and buggy when the snow was too bad,” Jim said. “In his 50 years (on the job), he only missed three times in delivering the mail.”

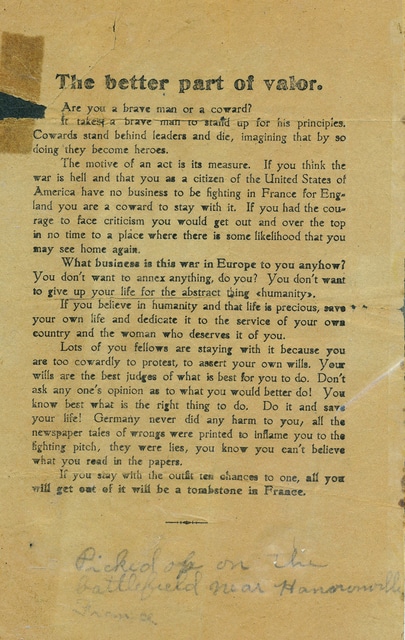

Jim now proudly displays in the Shelby County Historical Society’s Ross Historical Center, memorials of his grandfather’s service: Merton’s uniform and gas mask; his dog tags, pay record and discharge papers; a soldier’s shaving kit and piece of “trench art”: a pocket knife carved from a shell casing. There are also “souvenirs” from the Germans, including a German Army cross, German uniform buttons, a pocket knife and propaganda fliers, in English, which had been dropped from German planes on American forces, trying to persuade them to defect and change sides.

“It was an important war,” Jim said, “and one that we won. Based on my experience (in Vietnam), it was nice to know we won one once in a while.”