Blain isn’t a place most foreign tourists visit. It’s a small town in northwestern France, probably similar to many other towns in that country. There’s a church in the middle of the village, with buildings housing shops, restaurants and other businesses surrounding the town square. But 71 years ago, Blain was on the line that marked territory occupied by the German army to the west and the U.S. Army to the east.

After the D-Day invasion of June 1944, when Allied forces stormed the beaches at Normandy in northern France, surviving German troops that did not escape to the east were trapped west and southwest of Normandy along the Atlantic Coast. That’s where thousands of them still were in 1945. The American army was there, too, to keep the Germans from breaking out and attacking Allied forces from the rear as they pushed into Germany. These areas were called the St. Nazaire and Lorient sectors or “pockets.”

My father, Paul Seffrin, was among those American soldiers. A corporal with a field artillery unit, his job as a radio operator was to call in locations of German artillery batteries to American artillery so they could fire on the enemy guns and take them out.

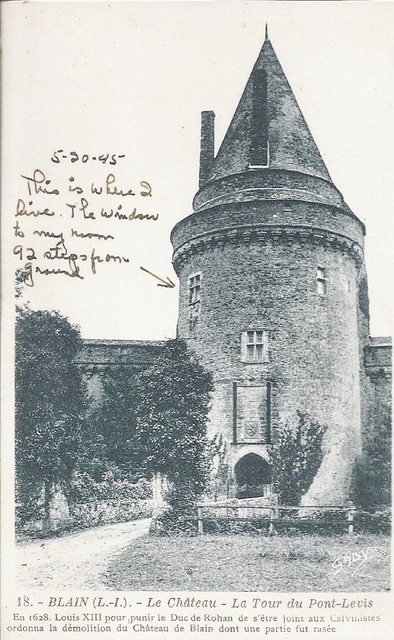

According to World War II military records I obtained from the National Archives, my dad’s unit patrolled in the area of Blain. After the war in Europe ended in May 1945 with the unconditional surrender of the Axis powers, his unit was stationed in Blain. The soldiers’ accommodations were in a castle that dated back to the Middle Ages. The castle was part of Le Chateau de Blain. The soldiers were housed in a tower in an outer wall above where a drawbridge over a moat had allowed access to the castle in earlier times. The moat apparently was filled in over the years and by 1945, a path led to the tower entrance.

My dad bought postcards depicting the castle and other features of Blain. On the tower postcard he wrote: “5-20-45 This is where I live. The window to my room. 92 steps from the ground.” He drew an arrow pointing to the window.

No matter how much our parents and grandparents tell us; no matter how much history we read, we really cannot know what their lives were like. But standing where they stood and imagining what they saw, adds another dimension to that understanding.

I was able to do that last summer during a trip to Europe. My wife, Bonnie, and I and our son, Patrick, and daughter-in-law, Susan Meyers, visited Paris, Normandy and Amsterdam.

In planning the trip, we had looked at a map of France and realized that Blain probably was just too far from Normandy for us to travel there in the time we had. Also, although I found in a search of the Internet that Le Chateau de Blain was still there, I couldn’t determine if it was open to the public.

I thought my World War II history experience would have to be confined to the D-Day beaches at Normandy — and that would have been quite impressive by itself. Located on a bluff above Omaha Beach (the bloodiest beach on June 6, 1945), the American Cemetery contains the graves of 9,387 U.S. military service members killed in the D-Day invasion and the battles that followed during the Normandy Campaign.

The immensity of that loss perhaps can be shown by one statistic printed in the cemetery brochure: The cemetery includes 45 sets of brothers.

We caught up with a tour guide who was talking to a group about the cemetery and memorial. He stopped at a wall inscribed with the names of 1,557 soldiers, sailors and airmen missing in action from the Normandy Campaign. Bronze rosettes have been placed beside the names of service members whose remains have been later recovered, identified and buried.

The guide pointed out one section of the MIA wall where many men from the 66th Division were listed. They were on a ship that was sunk in the English Channel by a German U-boat on Christmas Eve, 1944. The division’s soldiers had been assigned to serve as reinforcements during the Battle of the Bulge, but they never made it to that battle. Nearly 800 soldiers of the 66th were killed or missing from the U-boat attack. The sinking of the troop transport was the second largest loss of life from a troopship disaster in the entire European war, according to historical records.

Seeing the 66th Division men’s names on the wall made it personal for me. My dad’s unit was attached to that division. Had he been shipped over from the U.S. a couple of months earlier, his name might have been on that wall.

As you look over the fields of white crosses and Stars of David at the American Cemetery, you imagine not only the young lives cut short, but the things those individuals never had a chance to do, the sons and daughters they never had.

After our visit to Omaha and Utah beaches, my son and daughter-in-law decided we should go to Blain the next day. It would mean they wouldn’t see a different site that was on our original itinerary. They thought a visit to Blain would be more meaningful to me, and they were right.

Amazingly, Blain appeared much as it did in my dad’s old postcards. The church still dominated the town square and the buildings around it were still recognizable.

We got directions to Le Chateau de Blain from the operator of a small restaurant where we ate lunch. As we walked from the restaurant to the chateau, it was like moving back to 1945. The bridges over the canal, even the boats on the water, were similar to those in the old photos. We could see one of the chateau’s towers in the distance and took a path along the canal that connected to a narrow road that ran alongside the chateau’s outer walls.

We were happy to find that not only was the particular tower where my dad lived still there, but it was open to the public. I walked into an information tent near the entrance to the tower and tried to tell a young woman operating the booth why I was there.

“Mon pere ici (my father here),” I said, trying to remember my high-school French and showing her the old postcard depicting the tower. I was relieved when she started speaking English. I repeated my statement, “My father was here during World War II.”

She invited us to go up into the tower. Its interior had been restored to look as it did during the Middle Ages — after all, World War II was just one of many events the tower survived over the centuries.

When we reached the room where my dad had slept, I looked out the window to which he had drawn the arrow on his postcard and imagined him looking out the same window 71 years earlier. From the window, I saw a large field covered with tents and parked cars. It appeared a festival was under way. It occurred to me that the same field probably had been the site of many such events over the centuries, including jousting tournaments during the Middle Ages.

The tower room was dominated by a large fireplace. I could imagine my dad and his fellow soldiers standing near the fire to keep warm during the winter of 1945.

As we walked down the tower’s winding stairway, we counted the steps. There were 92. We knew we had found the right room.

The young woman at the information tent offered to take a photo of us standing in front of the tower. Afterward, she talked about World War II and its effects on this part of France. Even though the war happened many years before she was born, it is still a vivid part of history passed down from generation to generation.

The common belief among Americans is that French people are rude to American tourists. We found just the opposite to be true — even in Paris. As an example, my wife and I were standing on a street corner in Paris, looking at map, when a fashionably dressed woman (all Parisian women were fashionably dressed — it must be a city regulation) came up to us and asked if we needed help. She spoke English, of course. Most French people we encountered did. She told us how to get where we wanted to go. We said, “Merci,” (thank you is one of the few French words in our vocabulary) and moved on.

The French people we met not only were friendly; they remember what Americans did for them in two world wars. Because of those wars, more Americans are buried in France than in any other country except the United States, observed historian David McCullough, author of “The Greater Journey: Americans in Paris.” I suspect most Americans do not realize that. I suspect most French people do.

My dad died in 1981. He never returned to France to visit the place where he had served. I don’t know if he wanted to. Like most WWII veterans, he didn’t talk much about his war experiences. He was one of more than 16 million members of the U.S. armed forces during the war. According to the Department of Veterans Affairs, about 620,000 veterans of the war were estimated to still be alive as of 2016.

Americans are fortunate to not have lived under foreign occupation as the French did after the Germans invaded in 1940. The hardships under the Nazis, and the Americans’ role in ending that terrible period, perhaps were on the mind of the young Frenchwoman at the information tent as she spoke to us shortly before we left. Although she spoke English quite well, I could tell she was searching for the right words. In the end, it came down to one word.

“The Americans were very important to France,” she said, “because … freedom.”