America is built upon a cultural foundation of ambition and excellence. Four short stories involving physical challenges of endurance — a hazardous hike, a death march, and two long races — illustrate these traits.

Ohio, 1798. John Hosbrook, a Revolutionary War veteran from New Jersey, had hacked out a home for his family in the frontier wilderness. They survived largely on the abundant deer, bear, and small-game meat of the surrounding forest. But in the midst of a brutally cold winter, the Hosbrooks had run out of the salt needed to preserve their dwindling food supply.

Having hiked eight miles to a fort to replenish his supply of salt, John Hosbrook set out on the return trip — not knowing that a fierce blizzard awaited him. When winds began to whip through the forest and a heavy snow soon covered his path, Hosbrook knew he was in trouble. Each desperate step brought him closer to home but also closer to collapse. Exhaustion prevailed, John Hosbrook’s knees buckling beneath him as he plunged to the ground and soon froze to death.

John’s 13-year-old son, Dan Hosbrook, helped his mother cope with their tragic situation. In time, the family flourished, and Dan became the county surveyor, court sheriff, and a member of the Ohio Assembly. My mother was Dan’s great-granddaughter and grew up on the farm where her ancestor had perished a century earlier. My father’s from the same small village of Madeira, Ohio, and his best life-long friend was Howard DeMar, the postmaster of Madeira.

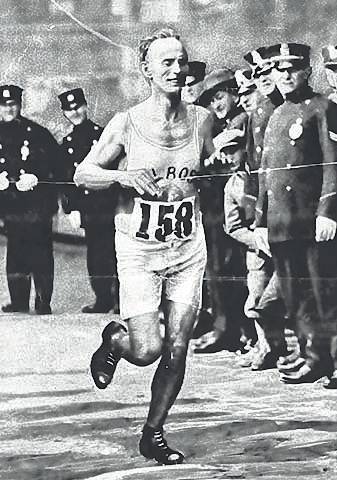

The Boston Marathon. Howard’s first-cousin was Clarence DeMar — who had a gift and a gait for running, chasing jack rabbits down the Madeira hills on his way to school. Clarence never stopped running, even to work as an adult. Someone suggested he enter the Boston Marathon. He did. He won the 1911 race but was advised by his doctor to give up running due to a heart murmur.

A decade later — and after his doctor had died of cardiac arrest — Clarence decided to risk running again. He felt fine, became a fierce competitor, and entered the 1922 Boston Marathon. He not only won, he dominated the race for the next eight years, winning six times between 1922 and 1930. Clarence holds the Boston Marathon record for most wins at seven and for being the oldest winner, breaking the tape just short of his 42nd birthday. The Boston Globe gushed that Clarence had “the most famous legs” in America, other than a well-known actress.

But the true greatness of Clarence DeMar was in the future, not the past — for he never quit running, running on forever, as it were, for the sheer fun and challenge of competing. He ran his last Boston Marathon at age 65 and his last road race at age 70, just months before dying of cancer. He was lauded for having “grace, grit, and gumption” and the versatility of being a printer, preacher, runner, scoutmaster, farmer, and scholar with a Harvard degree. Clarence DeMar epitomized the American spirit.

The Korean War. My brother was the captain of our high school football team, and his best buddy, Leigh Whitaker, was the play-by-play announcer for home games. Leigh was light-hearted, a fun guy, and gave my brother credit for all gang tackles, our school’s primitive public-address system crackling with Leigh’s voice proclaiming “yet another tackle by Bucky Burns.” Graduation came. War came. My brother ended up on a Coast Guard cutter in the north Atlantic; Leigh ended up in Korea, an army medic whose unit was overrun by a pre-dawn attack south of Seoul.

One of the few survivors and initially lined up for execution by a firing school, Leigh became a POW, a prisoner of war who was kept on the march and slept on the cold ground of Korea for over three years. For 37 agonizing months, his family only knew he was an MIA, missing in action. They didn’t know that Leigh was alive, had dropped to 85 pounds, and endured a final death march to the Yalu River near the Chinese border.

I was a freshman in high school, a radio junkie, and the only one awake in our house when I heard another voice crackling over the radio late at night. They were reading off one of the final lists of prisoners coming home from Korea. “Charles Leigh Whitaker, Cincinnati, Ohio.” Fighting tears, I jumped out of bed and woke up my parents and sister. “Leigh’s coming home.”

Like Clarence DeMar, Leigh’s life had a remarkable future as well as a past. He wed his high school sweetheart, Joyce Knippling, and, with her, raised two beautiful children — both with muscular dystrophy. Robbie, 7, and Kerrie, 6, were the 1963 National Poster Children for the Muscular Dystrophy Association. They were invited to the White House to meet President Kennedy, posing for a picture with the president (five months before his assassination) along with actors Jerry Lewis and Patty Duke in preparation for the annual M.D. telethon fundraiser.

The Boston Marathon. My story ends up back at the finish line of the Boston Marathon. But the year is now 2013. Competing in the disabled division is Kris Biagiotti, pushing her severely-handicapped daughter Kayla in a wheelchair designed for road racing. Kris took up distance running with Kayla shortly after her husband died of a heart attack. Known as Boston’s “K Girls,” Kris and Kayla do road races to raise funds for handicapped children. Again, there’s a family connection — my niece is Kayla’s godmother and Kris had recently attended our son’s wedding.

Kris and Kayla had circled the 2013 Boston Marathon in hopes of becoming the first mother-daughter duo to complete the storied race. But darker forces were at work, two terrorists having also circled the 2013 Marathon as a venue for expressing their hatred of America. Kris and Kayla would collide with the radicalized evil of the Tsarnaev brothers at the finish line.

Having conquered Heartbreak Hill, Kris and Kayla were approaching Copley Square as the Tsarnaevs placed their bombs on the sidewalk and melted away in the crowd.

The bomb placed directly behind a family of four exploded just seconds after Kris’ fiance, Brian, left that area to assist Kris and Kayla deal with a pool of reporters waiting to interview them. The shockwave of that first blast killed a little boy while severing the leg of his sister.

Shrapnel flew through the air like bullets. Brian was grazed in the head and bleeding as he helped Kris and shielded Kayla from the full force of the blast. Fortunately, they all survived, and Kris returned the next year to run the Marathon and defy the terrorists.

Epilogue. John Hosbrook; Clarence DeMar; Leigh Whitaker; Kris and Kaya. Each showed courage and endurance while contributing to the family stories that form our American mosaic. Everyone’s now doing DNA to trace their roots. But you may find interesting family stories if you look elsewhere — in old letters and stacks and scraps of family memorabilia before they’re thrown out; and in the minds and memories of older family members while they’re still here. Everyone has a story worth telling. What’s yours? Find it and write it down for future generations.