Editor’s note: February is Black History Month. In commemoration, the Sidney Daily News will run articles about area African Americans. If you have a story to share, call 937-538-4824.

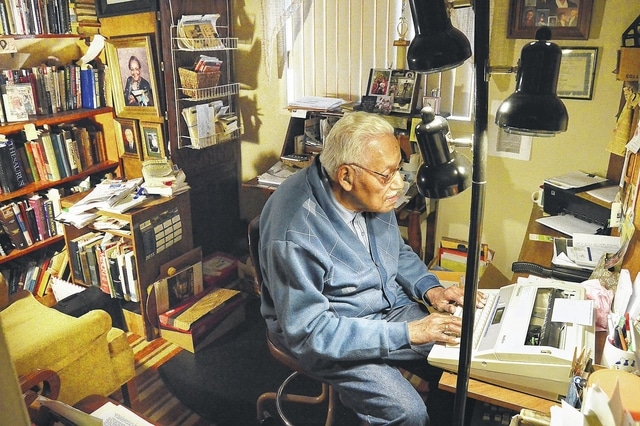

SIDNEY — Thomas G. Wall, of Sidney, is 90 years old.

He grew up in the 1930s and ’40s in Piqua, where, he said, institutional racism shaped and defined his whole life. He was born to black parents but his grandfather on his father’s side was from India. His great-grandfather was Jewish. And his grandfather on his mother’s side was white, from the Netherlands.

“I left Piqua in 1944. I was drafted just after I learned I wasn’t going to graduate (from Piqua Central High School),” Wall said. “The reason I didn’t graduate?” He recounted what happened to him one day at school those many years ago.

“I went to gym class,” he said. “There was a leak in the gym and the whole class had been sent to the YMCA, but not me. I was not allowed in the Y.”

According to Piqua Municipal Historian James Oda, the YMCA was, for the most part, white-only until after World War II. So were the movie theater and restaurants.

Barbers and beauticians had to serve either white or African-American clientele, not both. Black barbers could cut hair of white customers, but they couldn’t then also serve black customers.

By the time Wall was in high school, people at the YMCA were especially sensitive about not mixing races at their events.

“One of the examples in the teens was that someone in the Y allowed the Second Baptist Church (which had an African-American congregation) to rent the Y for a mass baptism. It was easier in the pool than in the river,” Oda said. When others at the Y found out about it, the pool was drained and scrubbed before any white members were permitted to swim in it.

Even though segregation began to break up at the Y and other facilities after the war, swimming did not become integrated until the late 1950s.

A segregated Y-sponsored club for boys, the Sepia Hi-Y, was disbanded in 1949.

But in the early 1940s, Wall could not join his classmates when the gym pipes sprang a leak. He and his physical education stayed behind.

“So I shot baskets by myself,” Wall said. “My hand got caught in the net and it ripped. (The teacher) told me to go to the janitor’s closet for a ladder to fix it and I refused. He came at me. I backed up to the wall. I hit my arm on a heat pipe. (To pull away from the burn), I threw my arm out (in front of me). He thought I was going to hit him. He sent me to the superintendent.”

Wall was suspended from school, even though his father was the superintendent’s barber.

The young Wall got a copy of his transcript.

“My transcript from my senior year had been fixed to keep me from graduating,” he said. It was his second experience institutional racism. His first had been when, as a child, he had hoped to be a newspaper boy.

“We don’t have ‘colored’ paper boys,” the Piqua Daily Call told him. He was also turned away when he applied for a job at Kroger.

The next came when he got to Fort Leonard Wood, Missouri, as an Army draftee.

“The ‘colored’ and the white were separated,” he said. “The ‘colored’ couldn’t be on the white side after 6:30 p.m.” He became the company clerk because he could type.

“Typing was my best subject in high school. The teacher said I had magic fingers,” he said. Following basic training, he was sent to New York City to learn electrical maintenance.

“I was paired up with a guy. We went to 7th Avenue. I looked up at the theater (marquee) and guess what was up there. The Mills Brothers,” Wall said. The Mills Brothers were a vocal group from Piqua who became world famous. Wall went to the stage door to find out if he could talk with them, but the stage manager told him that the brothers were not accepting visitors.

“I never got to meet them,” Wall said. He was excited in New York to climb the steps of a subway station and see his name on a street sign: Wall Street.

“I walked all along it. I felt good. I was a part of New York,” he said. He was on Times Square when news came that Franklin Roosevelt had been relected to the presidency in 1944.

“It was so crowded you couldn’t move,” he said.

He returned to Piqua when his stint in the Army ended and worked a series of jobs in local facorties. He applied to work at Kroger’s but was turned away. He met a girl, fell in love, got married and moved to Bellelfontaine. Eventually, he went to barber college in Cleveland and served his apprenticeship in his father’s shop. He opened his own shop in Bellefontaine.

“I was doing things in the barber shop that were aggressive,” he said. He extended open hours to serve farmers who could get afford the time to get a haircut only when it got too dark to continue work in their fields.

“Someone came and said, ‘Slow down, you’re too progressive,’” Wall remembered. He earned a nickname that he still carries today: Tom Cat.

“I cut little boys’ hair. They’d cry and I started to meow. ‘Meow. Meow,’ I’d say. And they’d stop crying,” he said. “So they called me Tom Cat.”

When he found that he could not be a member of the American Legion because of his skin color, he and joined with others to establish a black American Legion post, named after the first Logan County black man to die in World War II. It existed until the early 1980s.

“I became commander of the McGinnis American Legion post,” he said. “We had a dance and invited all the American Legions that wouldn’t let me in. It was something else. We locked arms. Black and white veterans eating together, sitting together. It thrills me still today,” he said.

After he closed the barbershop, which he said he was forced to do by city leaders who claimed he had not paid his taxes, although he showed them a receipt proving that he had, he moved to Sidney.

Times had changed in the intervening years, and he got a job at Kroger, where he worked as a clerk in the seafood department until he retired 20 years ago.

Married to his second wife, Mary, for the last 37 years, at age 88, he wrote a book about his life.

“At age 90, I am resting on my laurels,” he said.

Oda is philosophical about what Wall and other blacks experienced, that “institutional racism” of earlier decades.

“I’m not saying what we did wasn’t bad, but Piqua, Troy, Sidney, Dayton were all doing the same thing. But we weren’t a hot bed of racism,” he said.

Wall, too, is philosophical.

“God made us all alike,” he said. “Two front teeth — everybody has them. What He told us to do with those teeth: smile. A smile is the answer to everything.”