FORT LORAMIE — Michael Schiltz lived the kind of life books and movies are based on. He grew up in Berlin, now Fort Loramie, before going to fight in one of America’s bloodiest wars. He was captured, but through luck and will power he survived extreme starvation before making it back to Berlin.

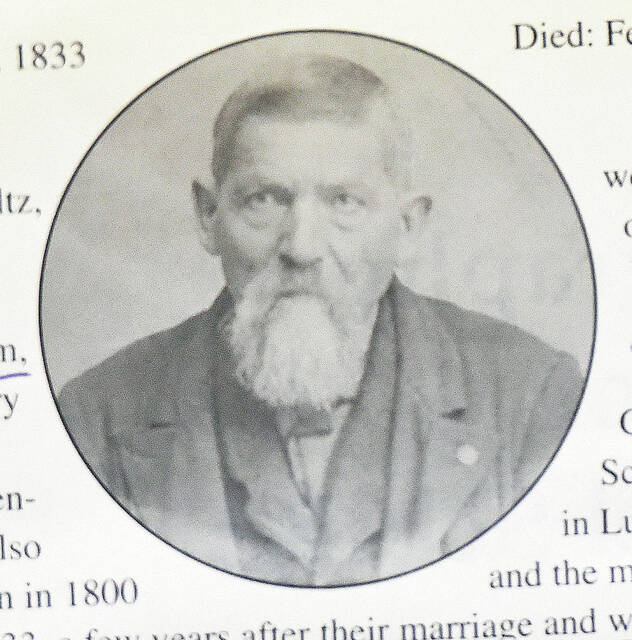

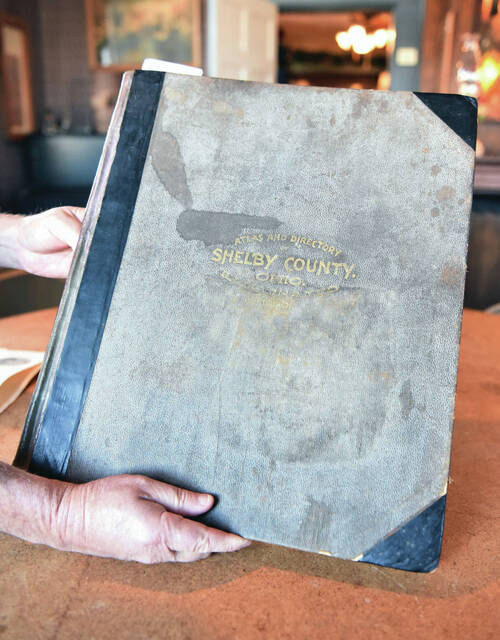

Flash forward to today. Schiltz’s great-grandson, Don Bollheimer, of Minster has worked to preserve the legacy of Schiltz by creating an informational pamphlet that he has distributed to friends and family. The pamphlet largely borrows its text from the Atlas and Directory of Shelby County, Ohio, illustrated in the year 1900. A photo of Schiltz and a short summary of his experiences in the Civil War can be found in a section of the atlas designated for Shelby County inhabitants.

Bollheimer’s mother, Anna Naber Bollheimer, was the daughter of Frances Schiltz who was the only child of Michael Schiltz.

Schiltz was born in Luxembourg which was, at the time, a province of Belgium, on Jan. 27, 1833. When Schiltz was 5-months-old his parents, Charles and Catherine Blowen-Schiltz emigrated to New Berlin in Stark County, Ohio. New Berlin is now called North Canton. In 1838 the Schiltz family moved from New Berlin to Berlin which had just been founded in 1837 and is now called Fort Loramie. According to a 1908 publication from the Ohio State Archeological and Historical Society, Charles Schiltz helped name the town Berlin along with J.M. Pilliod. The two named the town after their previous home in New Berlin.

Schiltz’s education consisted of classes in a log school house. In 1844 Michael’s dad, Charles, died leaving Michael as the man of the house at 11-years-old. As an adult, Michael made a living as a shoe maker and for 10 years he was a canal boat captain. In September 1866 he married Ann E. Roland who gave birth, on Sept. 14, 1869, to their only child, a daughter named, Francis. On April 1877 Ann Schiltz died.

In 1860, a photo of Schiltz and two of his friends appeared in a local newspaper. The photo jokingly depicts them elaborately dressed as cigar salesmen, each with a drink in hand. A year after the photo ran in the paper, Schiltz enlisted in the Union Army on Oct. 20, 1861. The Civil War had been raging for six months.

Schiltz was assigned to Company I, 40th O.V.I. Regiment. He was sent to eastern Kentucky where Schiltz took part in skirmishes which included Middle Bank and Pound Gap. The 40th Regiment was then sent to West Virginia where it encountered “rebel bushwackers” along the Kanawa River. His regiment was sent back to east Kentucky for several months before going to Franklin, Tennessee, where it took part in the first battle of Franklin, Tennessee. The regiment was working the picket line at the start of the battle and then moved to the main firing line causing significant casualties.

The regiment was then sent to Triune Tennessee where it engaged Confederate soldiers in a skirmish. They continued on to Shelbyville Tennessee engaging the enemy in skirmishes as they went.

They moved onward to Tullahoma, Tennessee, then marched to the Battle of Chicamauga.

Schiltz’s good luck was about to run out. The 40th regiment skirmished on September 18 and 19 before being sent as relief corps to the main part of the battlefield on September 20, 1863. After being in the battle for 45 minutes Schiltz had managed to capture a Confederate soldier and was taking him to the rear of the Union forces when he was accosted by Confederate General Nathan Bedford Forrest. Forrest emptied a revolver towards Schiltz, missing him with every shot.

At this point the confrontation with Forrest ended when the Union Army began advancing on their position while firing. Forrest retreated and Schiltz escaped. Schiltz’s freedom was short lived as he was captured just an hour later. This time there was no escape for Schiltz. He was initially sent to Libby Prison in Richmond, Virginia, for five weeks before being transferred to a prison in Danville, Virginia, for 6 months. While in the Danville prison, a man with whom Schiltz shared his blanket contracted smallpox and died. Schlitz never came down with the disease despite having to share the blanket even after the man became sick.

After Danville, Schlitz was transferred one last time to POW Camp Sumter, commonly known as Andersonville Prison in Georgia. Andersonville Prison was notorious for its treatment of Union Soldiers. There were no barracks to protect the prisoners from the elements. Prisoners were not provided the basic necessities for life such as adequate food, clothing, and sanitation. The prison was really just an open field surrounded by a stockade wall. A smaller inner wall, set 19 feet inside the stockade wall, created a no-go zone. Prisoners trying to breach the no-go zone would be shot by Confederate guards. The death rate was high with almost 13,000 of the camp’s 45,000 prisoners dying. Causes of death included scurvy, dysentery and typhoid fever. A small creek running through the center of the prison was a source of water and a toilet for prisoners.

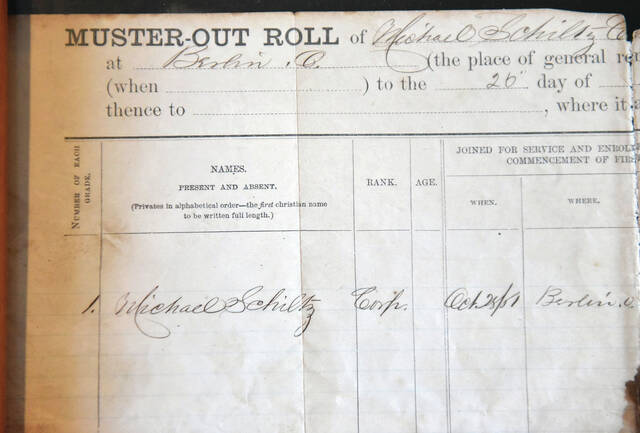

While Schiltz was at Andersonville Prison, a man he shared his blanket with died during the night. Schiltz spent the rest of the night next to the man’s body. In the morning the jailers were unaware of the death so Schiltz was able to receive the man’s breakfast ration. On April 1, 1865, Schiltz was released from Andersonville Prison, just 8 days before the end of the Civil War. Schiltz survived Andersonville Prison but it took its toll. He entered the prison camp weighing 165 pounds. When he was released he weighed 90 pounds. “He was promoted from private to corporal and later to sergeant for gallant and meritorious conduct on the field of battle.”

Schiltz was mustered out of the Union Army in Columbus, OH, on April 25, 1865. Shiltz’s muster out papers have been passed down by his descendants. The papers are currently under the care of Schiltz’s great great granddaughter, Carol Ranly, of Minster. Schiltz received $100 upon his release from the army according to the muster out papers.

After mustering out, Schiltz headed back toward Berlin on foot. As Schiltz neared Berlin, locals came out to welcome him back. He was offered a ride into town but he replied, “I’ve walked all this way, I may as well walk the rest of the way home.”

Schiltz didn’t go back to captaining canal boats. He switched careers, becoming a carpenter, which included making cabinets. After over 20 years of carpentry he retired. In July, 1881, Schiltz became a pensioner with a monthly rate of $6.00. The cause given for Schiltz being pensioned was scurvy and a resulting ulcer on his right leg, according to a list of federal pensioners compiled in 1883 by the Secretary of the Interior, Henry Moore Teller.

A few family heirlooms give glimpses of Schiltz’s life after the Civil War. An old button depicts an elderly Schiltz looking straight at the camera while sporting a long beard. Schiltz bought the personalized button while he was at a World’s Fair. A paperweight owned by Schiltz’s great great grandson Michael Bollheimer, of Fort Loramie, shows that Schiltz attended the 28th annual G.A.R. (Grand Army of the Republic) Encampment in Pittsburgh, PA. The gathering started in early September, 1894. The G.A.R. was a fraternal organization composed of veterans of the Union Army, Union Navy, and the Marines who served in the American Civil War. It was founded in 1866.

Another item that touched the hands of Schiltz is a large detailed drawing of the Andersonville Prison that he gave to the Vogelsang family which owned Vogelsang’s bar at the intersection of state Routes 705 and 66 in Fort Loramie. The Vogelsang’s hung the drawing in their bar for years until they sold the bar in 1983. The Vogelsang family kept the image and has leant it to the Fort Loramie Wilderness Trail Museum where it is currently displayed. Since the Vogelsang family purchased the bar in 1900, Schiltz would have given the Vogelsang family the image in 1900 or later. The bar was sold a number of times until it closed for good on Saturday, June 25, 2016.

On Sunday, Feb. 9, 1913, Schlitz died. The next day on Monday, Feb. 10, an obituary in the Sidney Daily News declared, “A Prominent Ft. Loramie Citizen is Dead.” The obituary went on to say he had died at his daughter Francis Naber’s house in Fort Loramie at 1 a.m., “of stomach trouble after an illness of about a month.” The obit gave a brief overview of his employment and his time as a Union soldier. A funeral service for Schiltz was held at St. Michael’s Church on Tuesday, Feb.11, 1913 at 8:30 a.m.