SIDNEY — It is one of the strange things about war. Nothing concerning it is predictable. War has a mind of its own. Your best buddy is here one day and gone the next.

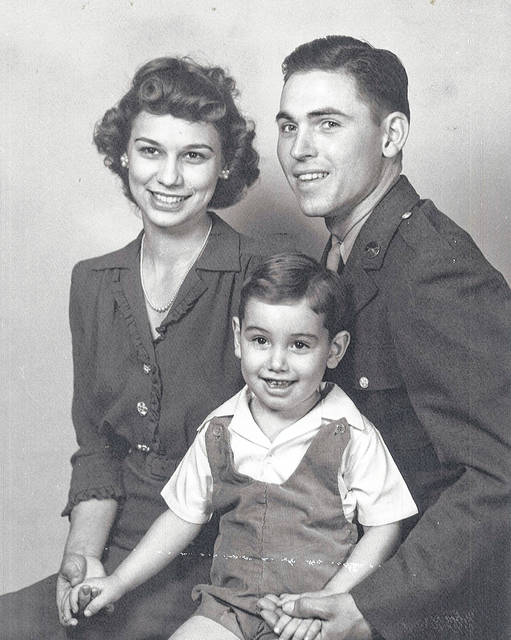

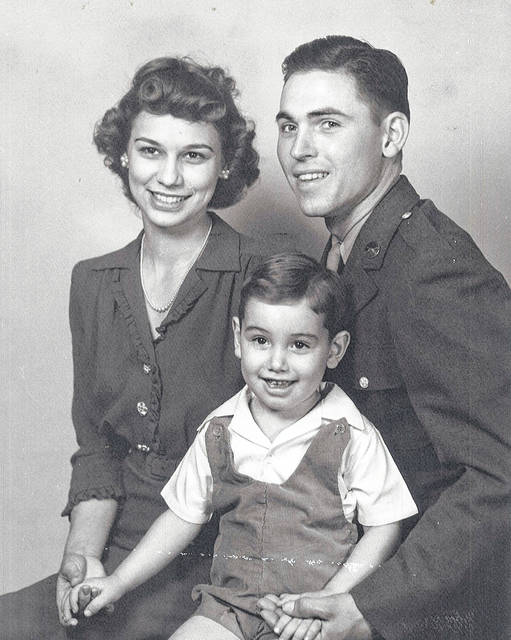

Virginia Fields thought the war thankfully had passed her small family by. It was the spring of 1944. Husband Chalmer had not been drafted. They checked the mail and read the paper each day looking for Chalmer’s name. It was not there. She thought little David, their two-year-old son was going to grow up knowing his father.

All that changed when Chalmer received the dreaded draft notice to report for duty. He left Sidney on June 28, 1944, with a number of Shelby County men, including George Zimmerman. They became fast friends. The men went by train to Fort Benjamin Harrison in Indiana. Zimmerman and Fields volunteered to help organize the arriving recruits. They were unexpectedly given a 24 hour pass for their efforts. On a whim, both men decided to hitchhike back to Sidney to see their families. Virginia recalled they arrived home “to our utter amazement.” Zimmerman’s wife drove them back to their base the next day. Perhaps the war would not be so bad after all.

It was July 6, 1944. The Louisville and Nashville (L & R) railroad train picked up speed as it approached the Jellico Narrows near Jellico, Tennessee. 1006 Army recruits were on board. It was 9 p.m. The men were just settling in for the night. Jackson Center native and Army recruit Richard Sailor decided to move from the kitchen or cook’s car to one of the troop cars. It was a decision which saved his life. Chalmer Fields also settled in for the night in his assigned seat in a car near the front of the train.

There was a relief engineer who should have met the train at its last stop in Corbin, Kentucky, before it headed south through the Tennessee mountains. But he did not show up. Train engineer Lyle Rollins, who started with the Army recruits, knew he was stuck with the next leg as well. Witnesses later said he was unhappy he had to continue with the train into Tennessee. Besides, after the delay to wait on the relief engineer, the train would be late – and that would reflect badly on him.

The train had picked up speed through the mountains approaching the Jellico Narrows. Suddenly there was pure chaos. The engine, tender and some of the cars plunged below into the gorge of the Clear Fork River. Twelve died instantly and more died in the days which followed. One could not imagine a worst place for a train wreck. The kitchen and baggage cars burned, and two coach cars turned over and burned. The river was a jumble of twisted metal, smoke, flames, steam and bodies. The engineer and others died because they were pinned underwater. Others burned to death from the steam. Some bodies were trapped under the cars, other bodies laid out over the flat rocks. Some survivors had to cross the river barefoot and stood there shivering. Those pinned were screaming.

Among the injured were county soldiers Fields, Zimmerman, Sailor, along with Leonard Zumberger, Ivan Coverstone and Lester Billing. Sidney recruits Ray Murphy and Harvey Blakely were on the train but not injured.

Virginia Fields and the other wives and mothers back in Shelby County had heard nothing when the army moved in and took command of the scene. Because of its proximity to the nearby Oak Ridge area of Tennessee where the nuclear bomb was being developed, there was a news blackout. Mrs. Fields and the others finally received a telegram advising them their loved one was injured and the Red Cross would be in touch. “The Red Cross people were wonderful,” she recalled.

A few days later they received travel passes to the area hospitals where the hundreds of men were being treated. The route they took via bus was U.S. 25. The road was full of twists and turns. Mrs. Fields recalled, “We traveled onward into the curvy, more mountainous area where the Clear Fork River runs through a deep gorge near the highway. The L & R railroad track ran 100 feet above the gorge.

“There we saw the wreckage of the 16 cars in the train. Eight were still on the track and the other eight were askew down the ravine, some telescoped on one another, all on their sides. Chalmer had been in a car near the front which had been split open by a car running over it. We were in shock!”

Fields had been pinned in the car by his feet. Battery acid dripped on him as he lay there, burning his back. He waited to be rescued, listening to the moans of his fellow soldiers.

As Virginia Fields was to learn later, although the Army arrived on the scene in the morning, the hero’s work had already been done. “When we got there it was just an awful mess,” a local resident recalled years later. Leo Lobertini was one of the first on the scene. He and his brother took their truck to the wreck, picking up as many miners as would fit in the truck along the way.

Local physician Dr. Ned C. Watts didn’t know the wreck had occurred until “a young man wearing only underwear briefs who was shouting” flagged him down. The local hospital had only one phone, so staff went to neighboring houses to call other doctors only to discover that Watts was the only doctor available. He spent several hours as the lone doctor at the wreck. Hundreds of Campbell County residents, mostly miners, flocked to the scene to help. They made the first rescues, using block and tackle slings to hoist the wounded up the side of the gorge to the road. It often took up to ten men to hoist a body up to the road. Some brought welding torches to free the trapped soldiers. A trucker who was passing through stopped to take a load of injured soldiers to the hospital. He came back and took several more loads. Volunteers continued to comb the river for dead and wounded. Later in the night, more doctors arrived from nearby towns. They went from car to car giving morphine injections to the trapped men. Many soldiers, their faces bleeding and dirty, waited for their more seriously injured comrades to be taken away before they received care themselves.

That morning, more organized efforts were put in place. Boy Scouts went door to door collecting shoes, clothes and sheets for the soldiers. Red Cross units served food on the Jellico hospitals lawn. A local restaurant closed in order to assist in preparing the food. Assembly lines were set up to make sandwiches, and local volunteers transported the food to the rescue site. Local groceries were emptied of bread. Many residents took in soldiers for the night, giving them food, a place to bathe and a place to sleep. The volunteers who had worked all night carrying the bodies out of the gorge eventually built a makeshift dam to lower the water level to retrieve bodies. They continued to work through the next three days. In all, 34 men died in the wreck and 75 were injured. There used to be a historical marker at the wreck’s site, but that has been stolen.

Many of the soldiers healed from their injuries and went on to serve in the war. Chalmer was released from treatment and received orders in December 1944. His first combat was on January 24th. His unit completed various assignments. The war for Chalmer ended when he received a serious bullet wound to his left elbow on April 11, 1945. He underwent surgery in England and arrived back in the United States on May 19th. The people who really remember the wreck are those who saw it and heard it. That was the case for Sidney Resident Jim Holloway. When the Sidney Daily News published an article about the train wreck on its 50th anniversary, Chalmer Fields heard of Holloway’s involvement and they met. Mrs. Fields was there. they were amazed to learn he had been one of the heroic miners who worked all night to save many men. “He had not talked about it at all until that moment,” Mrs. Fields recalled. “He could only talk and cry, even in my presence. He had done his ‘soldiering’ in a miner’s uniform.”

Jim Tidwell, a participant in the rescue effort, wrote a letter to the editor of the Jellico newspaper in which he described what he remembered when he thought of the wreck: “I see the troop train casualties stretched out on the rocks in the Clear Fork River and hear the ambulances once again as they wailed out screams, carrying the injured to the Jellico Hospital. I will see the engineer who was pinned under water with his hair waving at the surface. I will see a soldier who was finally freed from the wreck after several hours, sit down on a rock in the river, ask for a cigarette and then die. I will see the doctors working from coach to coach injecting morphine to ease the pain of those trapped.” To this day, Virginia Fields retains images of the mangled cars in the river and her beloved young husband Chalmer, lying in a hospital bed.

She will be 102 years old next month. Mrs. Fields understands the meaning of sacrifice.

The author wishes to express his appreciation for Virginia Fields and the summary she lovingly prepared about her experiences and the excellent article written by Phil Lea of Benton, Tennessee about the crash- the second deadliest train wreck during World War II involving U.S. troops.