Editor’s note: in conjunction with the 200th celebration of the establishment of Shelby County, the Sidney Daily News will be publishing a year long series about the county’s history.

SIDNEY — The ending of the War of 1812 did not mean peace on the Ohio frontier. Relations between the English and French were not good. England’s strategy of keeping the various Indian tribes in Ohio stirred up was working. Occasionally settlers were harassed, harmed and even killed by roving bands of Indians.

What is now Shelby County actually fared quite well in this regard for two reasons. Cephas Carey, perhaps the county’s most famous early pioneer, built a stockade on his property near Hardin. Area families gathered there whenever reports of Indians passing nearby were received. The other factor was Indian Agent John Johnston. He was experienced in Indian matters and well respected by all those who knew him. He used his considerable abilities to keep the Indians over whom he had influence in a peaceful frame of mind.

It promised to be another hot day. It was Aug. 18, 1813. As first light streamed through his cabin window, Henry Dilbone decided his wife and he would harvest the flax field. He prided himself in being an excellent spinner. His plan was to make the clothes he and his family would need for the coming winter from the flax.

A neighbor was a precious commodity in those days. When Dilbone and his family moved to Springcreek Township in about 1806, there was only one other settler in the entire township. Over the next seven years, George and John Caven, Benjamin Winans and William McKinney also purchased land in the township- make it a virtual population explosion for those years.

An uneasy peace settled over the Miami Valley after the end of the War of 1812. Over 6,000 Indians had settled near Indian agent John Johnston’s house, northwest of present-day Piqua. Almost all of them were peaceful, but there were a few troublemakers. Chief among them were two Shawnee — the famed Tecumseh and his brother — known as the “Prophet.” Tecumseh reminded the Indians the reward for a white man’s scalp was a princely sum paid by the British. He openly encouraged attacks on the white settlers.

Violence was no stranger to the Dilbone family. Henry’s family lived in Pennsylvania when he was born. His father John sold the family farm in 1786 and left for Baltimore with his life savings, including the money from the farm sale. When he did not return when expected, family and friends commenced a search. They found the 26-year-old John Dilbone shot dead. Henry, therefore, never knew his father.

Henry grew up determined to move to the Ohio Valley, buy some land and control his own destiny. He did just that. After marrying Barbara Millhouse in 1805, the Dilbones moved to the northern Miami Valley the next year.

As the sun rose on the fateful morning of Aug. 18, Henry had every right to be proud of what he had accomplished. He defaulted once on his payments and had to give the farm back to the government. After working for others to save money, he eventually re-purchased the 180 acre farm. Barbara and Henry had four beautiful children. They occupied a cabin on the east side of Spring Creek, just south of present-day Snyder Road. Life was hard, but good.

Besides seeing neighbors on occasion, the Dilbones were often visited by the Indians. They would trade deer and turkey meat for bread baked by Mrs. Dilbone. Henry enjoyed the visits. He did not mince words about Tecumseh and others who advocated violence against the settlers. Apparently, his opinions eventually reached Mingo George, a Shawnee generally regarded as one of the troublemakers.

When Henry and his wife left for the flax field on that morning, son John was left to tend to the other children. The dreadful events of that day were recalled years later in an interview with Albert Cory of Sidney’s Valley Sentinel newspaper.

The children settled down to play under the shade of a black walnut tree as Henry worked in the flax field. Suddenly, a shot rang out. Henry slumped to the ground, Mrs. Dilbone immediately ran toward the children, but the Indian swiftly overtook her. He split her head open with one smooth swing of his tomahawk. In the presence of her children, he proceeded to scalp her. The Indian then walked slowly toward the trembling children.

Young John Dilbone heard the report of another gun some distance to the south. Although he did not know it at the time, the gunshot was part of a coordinated attack. Other Indians had just shot and killed David Gerrad, one of the Dilbone’s neighbors, four miles to the south. John slowly turned to face the advancing Indian. Apparently fearful help was on the way, the murderer turned and began running away.

Neighbor William McKinney heard the shooting and arrived quickly. Henry Dilbone was still alive. He had been shot through the chest. Dilbone was taken to a blockhouse near Piqua. He clung desperately to life. Two days later, Henry asked to see the body of his wife. Henry died shortly after his grieving neighbors complied with his request. He was just 27 years old. Their bodies were secretly buried one and a half miles due west of where Fletcher, Ohio, is now located.

A party of determined men set out to find the murderers. Mingo George and his cohort escaped and traveled north into Shelby County. They stopped for dinner the next day at the Robert McClure cabin. It was located just north of what is now Houston. Only 16-year-old Rosanna McClure was home. Unaware of the Dilbone tragedy, she fed the Indians and sent them on their way. The Indians were fortunate. Rosanna had the reputation as an excellent marksman having killed a panther, six wolves, 22 raccoons and two deer in one winter.

Frontier justice was not long in coming. Gardner Bobo, formerly a militia captain in the Revolutionary War and a friend of the Dilbone family, secured the services of William Richardson. The latter was happy to help as he was the brother-in-law of the murdered Barbara Dilbone. Together Bobo and Richardson lay in wait for Mingo George where the present Miami-Shelby County line crosses the Great Miami River. He appeared at dusk on his way home from a grist mill on the river. They shot the Indian then used a long pole to punch his body into a quagmire near the river bank. Peace returned to the area.

Heart-broken neighbors raised the Dilbone children. Priscilla died at age 13. Margaret married Samuel Lindsay Jr. They settled nearby. John lived to an old age and eventually owned most of the family farm. William also made a living as a farmer. He subsequently moved to what is now Shelby County and settled in Perry Township.

When workers were paving the old Piqua-Urbana Road in 1918 (now U.S. Route 36), they uncovered human bones one and a half miles west of Fletcher. Cory Henman, a descendant of the Dilbones, was called to the scene to verify the location. It was the resting place of the Dilbones.

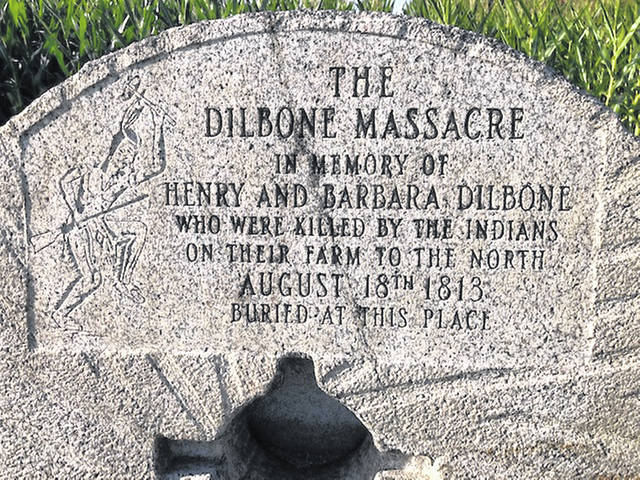

A memorial was created there in 1949 to commemorate the final resting place for the victims of the last Indian massacre in Western Ohio. Local historian Leonard U. Hill, of Piqua, closed the ceremony with these words:

“May all who view this marker be reminded that the present day comforts of life, the ease of acquiring a living and our assurance of security were not always thus. All of our pioneering ancestors endured many great hardships, and a few, as the Dilbones, made the ultimate sacrifice.”

The marker may still be seen on the north side of U.S 36 west of Fletcher.