SIDNEY — Military chaplains have been a part of American military tradition since 1775. General George Washington wanted chaplains to be religious leaders, but in addition, wanted them to help care for the wounded, bury the dead, write letters home for soldiers who could not read or write, and to offer sermons on the nature of patriotism to help prevent soldiers from deserting. The role made the chaplain a most important link in the chain of command between the commander and the troops.

At the advent of the Civil War, there was no set role for military chaplains. The selection of chaplains was left to the various denominations. The Union Army had 2,398 chaplains. Each chaplain was paid $100 per month and was issued a horse and an orderly to assist them in their duties.

The Union Army attempted to have at least one chaplain for every regiment. Initially, northern chaplains were only permitted by law to be from Christian denominations; that law was changed in 1862 to include “ordained ministers from any religious denomination” after protests from Jewish leaders.

Because of the lack of surviving records, the total number of chaplains serving the southern cause is unknown. It is known that Confederate President Jefferson Davis appointed 400 chaplains. It is thought that the total number was between 600-1,000.

Confederate chaplains were paid $85 per month. A number of chaplains serving the southern cause were “fighting chaplains.” The highest ranking of these was Episcopal priest and Confederate Brigadier General William N. Pendleton who was General Robert E. Lee’s chief of artillery.

Some commanders, notably Confederate General Thomas Jonathan “Stonewall” Jackson and Union General William Starke Rosecrans, were well known for their strong faith in God.

Author Donald McCleary has written that Ohio’s Major General Rosecrans, a convert to Roman Catholicism, conducted himself on the field as if he were a Crusader knight of old. General Rosecrans considered his most precious possession his Rosary, and he said the Rosary at least once each day.

“In battle the Rosary would usually be in his hand as he gave commands,” McCleary writes. “His personal chaplain, Father Patrick Treacy, celebrated Mass for him each morning. Father Treacy would busy himself the rest of the day saying Masses for the troops and helping with the wounded. In battle, Father Treacy would expose himself to enemy fire ceaselessly as he rode behind General Rosecrans. After military matters were taken care of for the day, General Rosecrans delighted in debating theology with his staff officers late into the evening.”

Civil War historian and author Stephen W. Sears has written that Virginia’s Lieutenant General Jackson was fanatical in his Presbyterian faith, and it energized his military thought and character. Theology was the only subject he genuinely enjoyed discussing. His dispatches invariably credited an ever-kind Providence.

“Assigning his fate to God’s hands, he acted utterly fearlessly on the battlefield — and expected the same of everyone else wearing the Confederate uniform. Jackson’s God smiled south, blessing him with the strength of Joshua to smite the Amalekites without mercy,” Sears has written. While biographers have either ignored or soft-pedaled this mercilessness in war, it underlines Jackson’s fierce battlefield leadership.

“This fanatical religiosity had drawbacks,” Sears has written. “It warped Jackson’s judgment of men, leading to poor appointments; it was said he preferred good Presbyterians to good soldiers. It branded him holier-than-thou, with an intolerance for others’ frailties, and this spilled over onto the battlefield to generate truly senseless confrontations with his lieutenants. One such, with General A.P. Hill, led Hill to rage at ‘that crazy old Presbyterian fool’ and seek to escape from Jackson’s command. Another lieutenant, reading in a Jackson dispatch that ‘God blessed our arms with victory,’’ remarked irreverently, ‘I suppose it is true, but we would have had no victory if we hadn’t fought like the devil!’”

Those who have visited the Gettysburg Battlefield may have noticed the bronze statue of Father William Corby, CSC. The bronze statue is placed atop the same boulder on which he stood while blessing the troops of the Irish Brigade on the second day of the Battle of Gettysburg, many of those men died just minutes later.

The statue of the Rev. Corby was placed on the battlefield in 1910, the first non-military statue to be erected at Gettysburg. Father Corby, a teacher at the University of Notre Dame, left the university to serve as a military chaplain, and returned to the university following the war, twice serving as president of that institution (1866-1872 and 1877-1881).

Perhaps the most noted of the Baptist “fighting chaplains” was Dr. Isaac Taylor Tichenor, who served as the chaplain for the 17th Alabama Infantry Regiment. In addition to being a respected religious leader and powerful preacher, he was a noted sharpshooter. He rallied the 17th Alabama at the Battle of Shiloh, preventing its rout and potential capture. Following the war, he became the first president of the Alabama Agricultural and Mechanical College (now Auburn University).

The only Catholic priest/chaplain to be killed in the war was the Rev. Emmeran Bliemel, a Confederate chaplain assigned to the 10th Tennessee Infantry Regiment. At the Battle of Jonesboro (Aug. 31, 1864), Father Bliemel heard the confession of his commanding officer, Colonel William Grace, who lay on the battlefield mortally wounded. As the Rev. Bliemel raised his hand to make the sign of the cross in final blessing, a cannon ball beheaded him, and he fell forward across the body of his regiment’s dying leader.

More than 620,000 men died in Civil War, more lives lost than American military casualties in WWI and WWII combined. Due to the nature of Civil War armaments, fighting on the battlefield was as fierce and bloody as death was slow and painful. Chaplains were there to offer spiritual guidance.

Chaplains slept on the same hard ground as the soldiers to whom they ministered, ate the same food, endured the same hardships, and confronted the same life and death issues. They visited hospitals, comforted the sick and dying, followed the army into battle, offered counsel and religious instruction, and did whatever was necessary – sometimes helping to carry the wounded from the field of battle, sometimes dressing wounds, sometimes assisting surgeons in field hospitals.

Certainly not all chaplains did their work well. One critic, Major General Benjamin Franklin (The Beast) Butler, himself one of the most colorful and reviled characters of the war, was called to offer testimony before The Joint Committee of Congress on the Conduct of the War In 1863. During his appearance, a lawmaker posed an unusual question: “What has been your experience in regard to chaplains?”

“The chaplains, as a rule, in the forces I commanded, were not worth their pay by any manner of means,” Butler testified. “(But) I am bound to say that I have never seen a Roman Catholic chaplain that did not do his duty, because he was responsible to another power than that of the military. They have always been faithful, so far as my experience goes. They are able men, appointed by the bishop, and are responsible to the bishop for the proper discharge of their duties.”

Despite Butler’s criticism, most chaplains performed their duties. While their work is not often celebrated in the pages of history, it is presumably celebrated in Heaven, for many of the estimated 3500 military chaplains who served the Union and the Confederate armies served both God and their fellow soldiers well.

Photo captions:

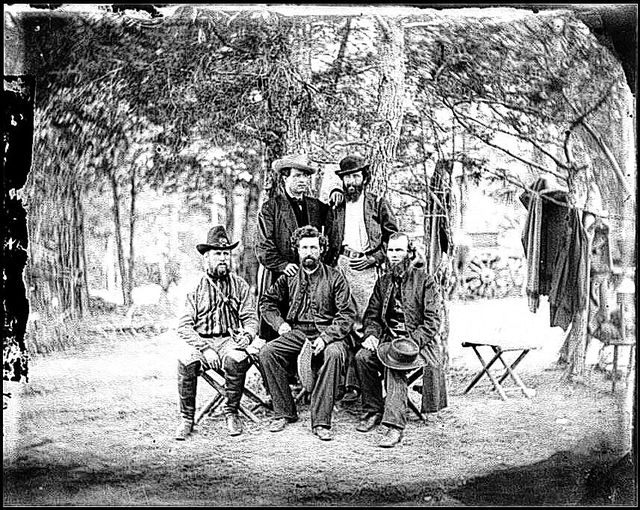

Notre Dame’s Civil War Chaplains with two officers from the Irish Brigade at the Union Army camp at Harrison’s Landing, Virginia, during the Summer of 1862. Sitting: Captain J. J. McCormick; Father James Dillon, CSC; and Father William Corby, CSC. Standing: Father Patrick Dillon, CSC, and Dr. Philip O’Hanlon. Photo by Alexander Gardner, official photographer of the United States Army. Original glass negative is housed in the Library of Congress.

Episcopal Priest the Rev. William Pendleton returned to his pulpit following the war at Grace Church in Lexington, Virginia. He would hold that rectorship for the rest of his life. He was instrumental in persuading his former commander, Robert E. Lee, to move to Lexington and assume the presidency of Washington University, the institution that is now known as Washington and Lee University. Pendleton conducted Lee’s funeral service in 1870, and spent much of the rest of his life traveling throughout the south, raising money to build the Robert E. Lee Memorial Church. In what can only be considered ironic, the first service to be conducted in the completed church was Pendleton’s funeral in 1883.

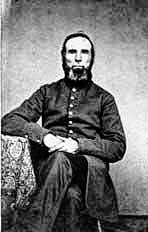

Baptist minister Lewis Raymond, chaplain of the 51st Illinois Volunteer Infantry, served for more than three years ministering to the needs of the regiment.

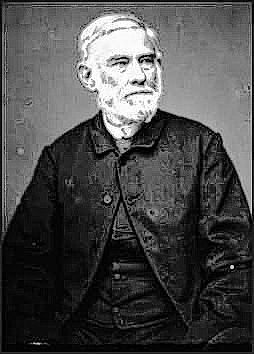

Presbyterian minister Nicholas Davis of the 4th Texas Infantry Regiment, served his men as part of the Army of Northern Virginia fighting in every major battle except Chancellorsville.

This photo of Major General Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson was taken on April 6, 1863, just days before he was accidentally shot at Chancellorsville. Jackson is considered to be one of the most gifted tactical commanders in American history. His generalship in the Valley Campaign and at Chancellorsville are studied worldwide as examples of innovative and bold leadership.

Ohio’s General William Starke Rosecrans commanded the Army of the Cumberland until his defeat at the Battle of Chickamauga in 1863. Rosecrans’s conversion to Catholicism while a student at West Point so inspired his brother Sylvester that he converted as well, and became the first Bishop of Columbus.