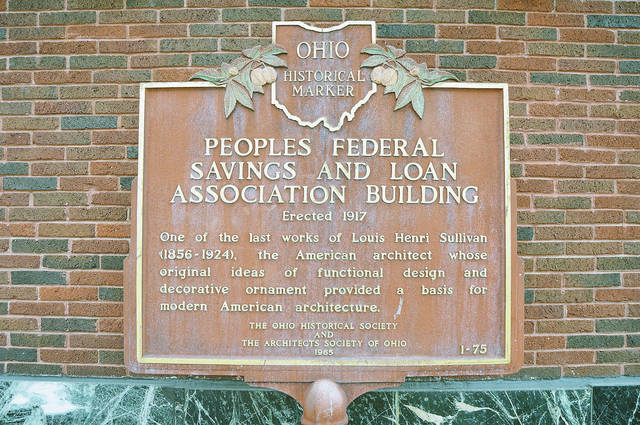

SIDNEY — Area residents have long known they have an architectural gem in their midst.

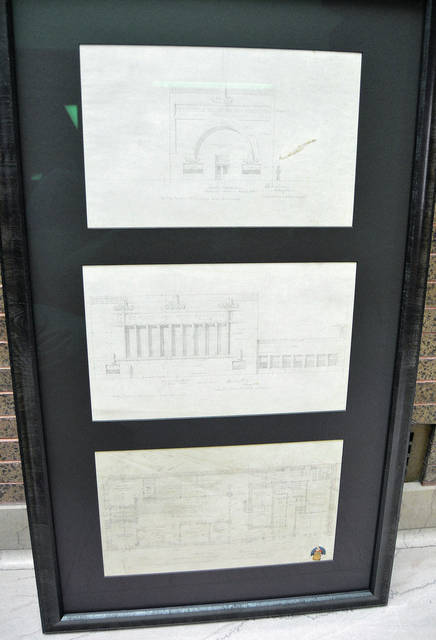

People’s Federal Savings and Loan Association will celebrate the 100th anniversary of its iconic building, May 31, from 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. An open house will feature refreshments and small souvenirs, and staff members will talk about the work of art they inhabit. On display will be historic photos and pencil drawings by the building’s brilliant designer.

It was May 31, 1918, when the staff of the People’s Savings and Loan Association — the “Federal” was added later — moved into the bank, the seventh of eight by renowned architect Louis H. Sullivan in the twilight of his career.

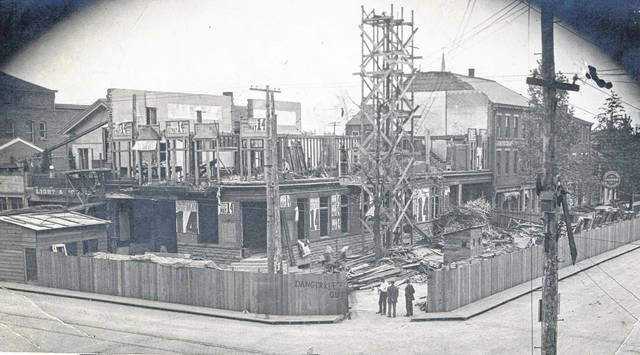

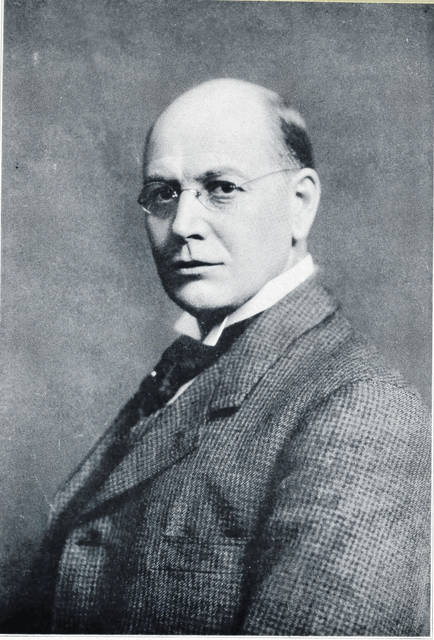

A year earlier, the famous — and some would say infamous — architect had sat for two days on the Sidney courtsquare, staring at the space comprising 101 E. Court St. It had been L.M. Studevant, secretary and founder of the bank, who had commissioned Sullivan to design the building. Studevant had seen a Sullivan bank in Newark and liked its style.

“It blows my mind that these people did that. Who gets someone like Louis Sullivan now?” said current bank President and CEO Debra Geuy, recently.

At one time, Sullivan was the premier architect in Chicago. He mentored Frank Lloyd Wright, and, with his partner, Dankmar Adler, designed America’s first skyscrapers. By the time Studevant contracted him, his style had fallen out of favor. Major commissions had dried up. It was the small town, midwest bank designs that were keeping the roof over his head. And even those designs were controversial. They didn’t include the grandiose Greek-columned facades that were the fad of the day.

In Sidney, Sullivan sat, chain-smoking cigarettes and staring across the street, devising the plans in his head.

“He rapidly sketched out what the building would look like,” said Geuy. “He showed it to (the board). One director said, ‘I fairly thought that we would have Greek columns.’ Sullivan stood up, rolled up the plans and said, ‘You can get a thousand architects to design that for you. I’m the only one who can give you this.’”

The bank was built without a single departure from Sullivan’s original plans. And unlike most of the other banks he designed, very few changes have been made since the savings and loan staff opened it for business 100 years ago.

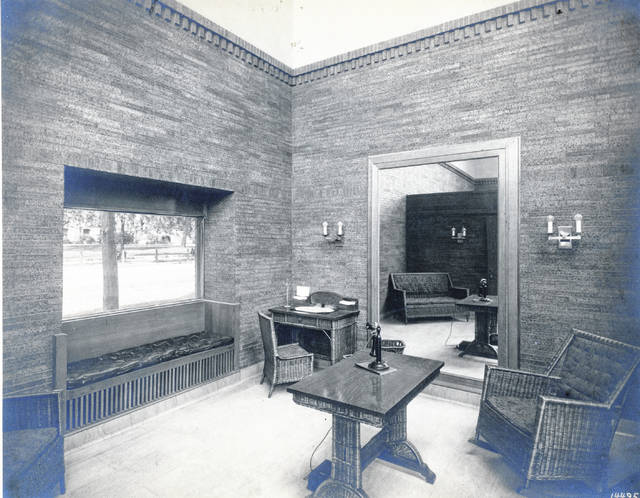

The original teller stations were behind glass and featured iron grillwork that has been removed. Additonal lighting was installed in the main room, probably when “bankers’ hours” were extended beyond midafternoon into a darker evening. The electricity and air conditioning have been upgraded to 21st century standards. Yes, 100 years ago, the bank was air conditioned.

“It was called an air washing system. It pulled air through ductwork and would shoot a mist through (large, decorative urns that are still in place at the north end of the business area). It didn’t work well. It was just adding humidity to an already humid, Ohio day,” said Gary Fullenkamp, vice president and corporate secretary. The ductwork, however, was just what was needed for the current air conditioning system. The 21st-century cooled air moves easily through the early 19th-century ductwork. Warm air still comes from the original radiators, although the boiler was replaced some years ago.

Also still in place and functioning are the cabinetry at the teller stations and tiger oak storage cabinets in the rear part of the building, heated benches for the public and a water fountain.

“Louis was very particular,” Geuy said. “He would reject any material if it didn’t meet his specifications. He rejected three drinking fountains before the one we have.” As the story goes, Sullivan sat on a nail keg, in the midst of the construction, the circle of cigarette butts collecting around his feet, supervising — today it would be called micromanaging — every aspect of what contractor H. Lafayette Loudenback did.

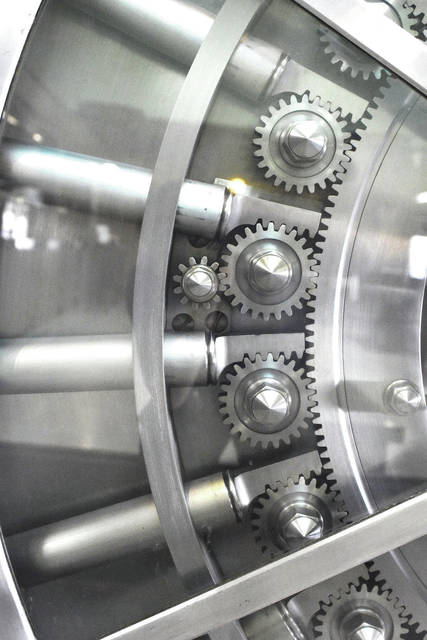

The huge, 11-ton vault door is the focal point of the bank. Sullivan is supposed to have asked bank directors if the vault would be open during business hours. When the answer was yes, he offset the vault so the opened door would be in the center of one’s line of vision, a tangible illustration of the safety in which ones deposits would be kept.

People have come from around the world to see this “jewel box” building. It’s been up to bank staff and directors to maintain it.

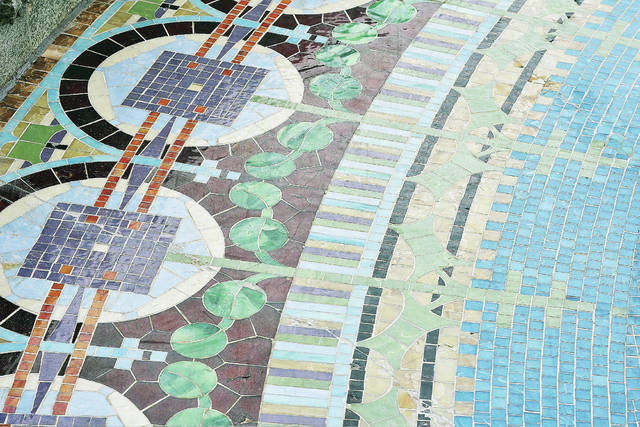

“This building is like an onion,” Fullenkamp said. There are layers and layers of artistic treasures to discover, appreciate and preserve.

“Definitely, there’s more expense to maintaining a 100-year-old building,” Geuy said. Every seven years, the brick is tuckpointed. More often than that, the terra cotta ornamentation is sealed. A greenhouse structure over the skylights protects them, but last year, conservators scraped off rust and sealed cracked glass that can’t be replicated.

In the not too distant future, the irreplaceable stained glass windows will need to be cleaned and refurbished. That will cost thousands and thousands of dollars.

“We’ll have to establish a foundation (and solicit donations) to do that. We do what needs to be done, always,” Geuy added. “I’ve worked in this building a long time, 40 years. But as president, I feel personally responsible. The people who have been responsible to maintain and protect this building have all been completely dedicated to doing that. It gets in your blood.”

Studevant and his fellow directors went to Sullivan because they wanted a building that would have a lasting impact on the community. They got it. One hundred years later, their legacy still serves and delights local banking customers — and art lovers from around the world.