Editor’s note: in conjunction with the 200th celebration of the establishment of Shelby County, the Sidney Daily News will be publishing a year long series about the county’s history.

Following the Revolutionary War, American settlers began moving into the Northwest Territory (the future states of Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Michigan, Wisconsin and a part of Minnesota). The land had previously been claimed by Great Britain. As a result of America’s victory over the British in the war, America’s claims to the land, while still contested by both Great Britain and France, opened the doors for settlement in the minds of many Americans.

In fact, the young nation was land rich and cash poor. Lacking the funds to pay the soldiers who served in the Continental Army, huge tracts of land in Ohio were set aside as payment in lieu of cash for soldiers who had served. That’s one reason that today we find the graves of soldiers who served in the Continental Army buried in Shelby County.

As American settlers moved into the Northwest Territory in the years following the American Revolution, their advance was opposed by a loose alliance of mainly Algonquian-speaking peoples. Both the Shawnee and Delaware had been driven west by prior territorial encroachments.

Historically, the Shawnee were a semi-migratory people, following animal populations throughout the winter months and establishing more permanent villages in the summers where women planted and harvested crops and the men hunted and served as warriors. They originally lived along the Ohio River as well as in Virginia, the Carolinas, Alabama, Pennsylvania and Maryland.

The Delaware originally lived in villages and engaged in agriculture and hunting. They would move after the soil in the area in which they were living had become depleted, moving but a short distance before erecting a new village. They originally lived in the present states of Delaware, New York, New Jersey and Pennsylvania.

The Delaware were the first tribe to sign a treaty with the United States (Sept. 17, 1778). This treaty forced them to migrate westward into Ohio.

By the end of the 17th Century, the Shawnee had been forced out of Ohio by the Iroquois Indians. They would return only after the signing of the Treaty of Grande Paix (Aug. 4, 1701).

Both the Shawnee and the Delaware joined the Ottawa, Ojibwa, Miami and Potawatomi in the Northwest Indian Confederation. Formed and led by Little Turtle, the Native American confederation engaged in a series of skirmishes with settlers and militia.

It is important to know that in the 18th Century the United States Army was quite small. Concerns over economy and the threat that a large, standing Army might pose to liberty led many Americans to regard the Army as a necessary evil. Fortunately, the relative security afforded by vast oceans and a sparsely populated country allowed the United States to survive with a minuscule military establishment.

In an effort to “pacify” the settlers in the territory and stake a conclusive claim to region that had been ceded by the British under the terms of the Treaty of Paris (Sept. 3, 1783), President George Washington dispatched Gen. Josiah Harmar to the region. With 320 regular troops and 1,133 militia from Kentucky and Pennsylvania, Harmar’s forces were decisively defeated in battles fought Oct. 19, 20 and 22, 1790.

The series of engagements did not begin well. On Oct. 19, Col. John Hardin led a group of 180 militia and 30 regular troops that was attacked on three sides. Most of the militia fled when the Indians first attacked. Only eight regular troops survived the battle. Forty militia were killed and 12 wounded.

The final engagement is usually referred to by military historians as Harmar’s Defeat. Again led by Col. Hardin, the engagement began with 60 regular troops and 300 militia. Although Hardin requested reinforcements, fearing defeat, Harmar kept his 800 remaining troops out of the battle.

Fourteen officers and 115 enlisted men were killed. Another 94 were wounded. More than 83 percent of the regular troops were casualties.

That final engagement was called the Battle of the Pumpkin Fields by the Indians. The steam from the scalped skulls reminded the Indians of squash steaming in the autumn air.

Frustrated, Washington ordered Gen. Arthur St. Clair, governor of the Northwest Territory, to march against the Indians. While Washington was adamant that St. Clair march north during the summer months, both logistics and supply problems slowed his preparations.

The new troops were poorly trained and disciplined. The rations were in short supply and of poor quality. There were few horses and those that were available were not well-suited for military service. The expedition didn’t set out until October.

When St. Clair departed Fort Washington (Cincinnati), his army included 600 regulars, 800 six-month conscripts and 600 militia. Desertion took its toll, and when the force reached Fort Jefferson (Hamilton), it had already dwindled to 1,486 men and approximately 250 camp followers (wives, children, laundresses and prostitutes). Going was slow, and discipline problems were severe.

By the time the army had reached the site of present-day Fort Recovery, the army had been reduced to 52 officers, 968 enlisted personnel and approximately 200 camp followers. On Nov. 4, 1891, a native force of more than 1,000 led by Little Turtle and Blue Jacket attacked. What ensued was the worst defeat ever suffered by the United States Army with a casualty rate of 97.4 percent. The casualty rate did not include the camp followers, nearly all of whom were killed and scalped.

Both generals had served in the Revolutionary War and were trusted by Washington. Harmar had served with Washington at Valley Forge. After the war, St. Clair had served as president of the Continental Congress. Neither would command troops again.

Washington next tasked Gen. “Mad” Anthony Wayne, who had also served with him at Valley Forge, with subduing the Indians. Wayne had retired to civilian life and served as a member of the House of Representatives in the Second Congress.

The American Army was reformed as the Legion of the United States. The army was composed of professionally trained soldiers, rather than state militias. The Legion was composed of four sub-legions each with its own infantry, cavalry, riflemen and artillery.

At the time of the Battle of Fallen Timbers, each sub-legion numbered approximately 500 men. Wayne’s army was buttressed by 1,000 well-trained mounted Kentucky riflemen.

The Legion of the United States met the Indian confederation’s warriors near Fort Miami (southwest of Toledo) at the Battle of Fallen Timbers on Aug. 20, 1794. Amid fierce fighting in a tangled wilderness of trees that had previously been felled by a tornado, Wayne’s troops broke the Indians’ line, and the warriors fled.

The Indians’ defeat was compounded by the fact that the British signed the Jay Treaty (Nov. 19, 1794). As part of the treaty, Great Britain promised to evacuate its forts in the Northwest Territory. Beaten in battle and with no prospect of outside assistance, the confederation agreed to meet to discuss terms of peace.

On Aug. 3, 1795, Wayne, Little Turtle and their delegations met at Fort Greenville to conclude the treaty. Both sides agreed to a termination of hostilities and an exchange of prisoners, and Little Turtle authorized a redefinition of the border between the United States and Indian lands.

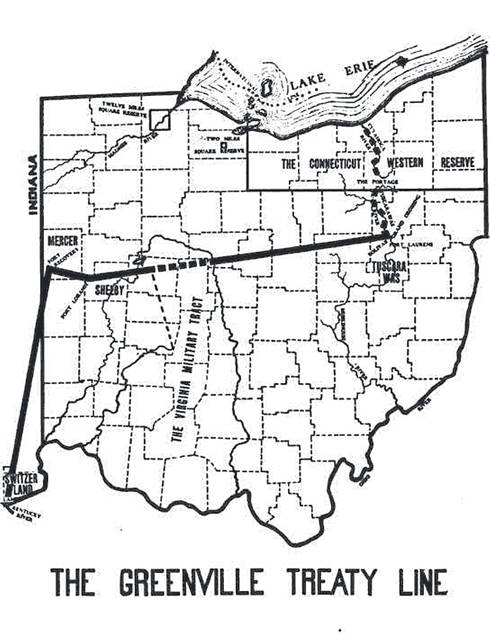

By the terms of the treaty, the confederation ceded all lands east and south of a boundary that began at the mouth of the Cuyahoga River, extended south to Fort Laurens and then west to Fort Recovery. The boundary then continued southwest to the point at which the Kentucky River emptied into the Ohio River.

In addition, the United States was granted strategically significant parcels of land to the north and west of this line, including the sites of the modern cities of Fort Wayne, Indiana; Lafayette, Indiana; Chicago; Peoria, Illinois; and Toledo. The treaty also ceded Mackinac Island and the surrounding land as well as a large tract of land encompassing much of the area of modern metropolitan Detroit.

The signing of the treaty ended the Northwest Indian Wars. It was signed by 89 Indian chieftains representing the Wyandotte, the Delaware, the Shawnee, the Ottawa, the Pattawatimas of Huron, the Pattawatimas of the region of the Saint Joseph River, the Chippewas, the Miamis, the Kickappos, the Kaskaskias and a representative of the Six Nations.

Signing the treaty on behalf of the United Sates were Gen. Wayne and 25 others. One of those signing for the United States was Wayne’s aide-de-camp and future president William Henry Harrison.

The Treaty of Greenville was important because it established what became known as the Greenville Treaty Line — a set boundary of the lands reserved for Native Americans and the lands open for American settlement. Representatives of the various tribes officially gave up their claims to roughly two-thirds of the land between Lake Erie and the Ohio River. In exchange, the Indian tribes received clothing, utensils, agricultural implements and animals worth $20,000 and an annual annuity of $9,500 in goods.

Despite the treaty’s promise, settlers continued to settle on lands reserved for the Indian tribes. The size of the American Army and the length of the Greenville Treaty Line simply made it impossible for the Army to enforce the provisions of the treaty.

Although Native American leaders including Tecumseh continued to attempt to regain their lost lands, settlers eventually outnumbered the Indians and ended up taking over their entire lands. In fact, the Treaty of Fort Greenville was only one of more than 500 treaties entered into by the United States government with Native American tribes, all of which were broken.

As noted previously, the Greenville Treaty Line passed through what is now northern Shelby County, extending westsouthwest from Fort Laurens in Tuscarawas County to Fort Loramie and from there west-northwest to Fort Recovery. The treaty opened much of what is today Shelby County to settlement.